Latest News

Kitchen Chat and more…

Kitchen Chat and more…

There isn’t much information that I could find online about Dramfool. What I do know is that Dramfool is the brand name of an independent bottler and that the owner’s name is Bruce Farquhar. According to Bruce’s LinkedIn Profile, he is an experienced engineer who is now the director of Dramfool.

This review focuses on one of Dramfool’s recent releases for the Islay Whisky Festival Exclusive Bottling that happened to be Dramfool’s 13th release. It is a Port Charlotte, distilled in December 2001 and bottled in December 2016. Dramfool bottled the whisky at cask strength of 58.3%. There are only 195 bottles available.

How does it taste like? Let’s find out.

Colour: White wine

ABV: 58.3%

Nose: The first notes I got was coastal salt and peppery spice. There is light vanilla cream in the background. Sweet barley notes surface after a few minutes. Gentle peat (soot?) wafts into the nose after 10 minutes, and lemony notes appear underneath the peat. (17/20)

Palate: Sweet barley comes quickly but peppery spice attacks right after the sweetness. After the spice mellows, coastal salt, vanilla cream and lemon notes appear all in succession. The gentle peat comes at the back of the throat. (16/20)

Finish: Medium finish with sweet barley and hints of vanilla. (16/20)

Body: It is a balanced dram with a typical Port Charlotte profile. It is decent, but not something that I would wow over. It is probably not something that I would want to spend money to buy a bottle. Nonetheless, Dramfool sounds like an interesting IB, and I would want to explore more of its releases. (33/40)

Total Score: 82/100

Geek Flora: “Well, it was a nice dram, but not something that gets me excited. A typical Port Charlotte profile is pleasurable but not fantastic. I guess I was looking for more as I had a great experience with the MoS Port Charlotte previously. You can find our review here“

Geek Choc: “Port Charlotte was not high on my list usually, and this is no surprise. I think it is a simple dram, balanced but not complex enough.”

What is it with rums, anyway? Whisky drinkers may or may not like rums for its sweet notes. However, rums are popular amongst many, and it is understandably so. Whisky makers are also increasingly using rum casks to age whisky to capitalise on the sweet notes that rums are famous for.

Rum is made from either sugarcane juice or sugarcane by-products such as molasses through a process of fermentation, distillation and ageing in oak barrels. The method of making rums is similar to whisky; the difference is in the ingredients. Most of the world’s most famous rums are from the Caribbeans and Latin America. However, there are many other countries which produce rums, such as Japan, New Zealand, Spain, South Africa, Taiwan, and the United Kingdom.

Rums have different grades. Typically, there are three grades of rums, light (white) rums, dark rums and spiced rums. They are consumed or used in different ways depending on the style that they are made. For example, dark rums are usually consumed on the rocks, or neat, or in a cocktail. Light rums are commonly only used in cocktails, but in modern times, some premium light rums are also drunk on the rocks.

Rum has connections in the maritime industry as it was used as a form of medicine in the past for the armies as well as the pirates.

While there are typically three grades to categorise rums, the grades and variations in describing rum dependents largely on the location of its origins. These are some of the most frequently used terms to describe rums.

There are also other varieties of rums that are lesser known, such as the flavoured rums and premium rums.

Flavoured rums are fruits-infused liquid and generally less than 40% abv. They are used for flavouring in cocktails and sometimes, drunk on their own.

Premium rums are a class above the rest of the rum categories. Similarly to premium whiskies, boutique brands craft them with more flavours and characters. They are generally consumed neat or on the rocks.

The production methods differ widely in the rum industry. The traditional styles of a particular locale determine the production method. Nonetheless, rum is made through a similar process as whisky. Rum producers also ferment the basic ingredients – molasses or sugar cane juice using yeast and water before distillation and ageing.

Molasses, the by-product of sugar cane, is the most common ingredient used to make rum. Some producers use sugar cane juice, notably from the French-speaking islands in the Caribbean. A rum’s quality is highly dependent on the quality and the variety of the sugar cane used. In turn, the quality of sugar cane is dependent on the soil and climate it grows in. Therefore, it is usual for rums to differ widely in quality in different places of origins.

Molasses (or sugar cane juice), yeast and water are the three ingredients for fermentation to take place. There is variation in the yeast used as well. Some producers use wild yeast, but most of them use a particular strain of yeast to ensure a consistent taste and stable fermentation time. The yeast used is essential as it will determine the final flavour and aroma profile. Lighter rums use quick yeast while the more flavourful ones tend to use yeast that is slower.

There is no standard distillation method. Some producers who make small batch rums use pot stills while most producers use column stills for distillation. The only difference between pot stills and column stills distillation is that pot stills create fuller flavoured rums.

Interestingly, most rum-making countries require producers to age their new-make rums for at least one year. The ageing is done in a charred, ex-bourbon oak barrel or a stainless steel tank. The ageing process gives rum its colour. It becomes dark when aged in an oak cask and remains colourless if aged in stainless steel tanks.

Due to the warm climates in most rum-making countries, rum matures much faster than whisky. The angels’ share of rum is also higher. It goes up to as much as 10% in tropical countries!

The final step in rum-making is to blend the rums for consistent flavours before bottling. Parts of this blending process include filtering light rums to remove the colour taken from oak casks and adding caramel to adjust the hue of dark rums.

It appears that rum and whisky have nothing in common when you first started reading, but it turns out that they have a lot in common. While the production methods differ, the general idea of fermentation, distillation, ageing and vatting (blending in the case of rum) is similar. In a modern world where traditional sherry casks are getting more expensive, it is no surprise that whisky makers are turning to other alternatives such as port casks, rum casks and wine casks for whisky maturation.

Rum casks infused a sweet overtone to the whisky and gave a robust body to it. We enjoyed some rum cask-finished whiskies, like the Glenfiddich 21 years old. If you love rums as much as you love whisky, be sure to give them equal attention as whisky makers who use rum cask for their ageing depend on you to drink more rum!

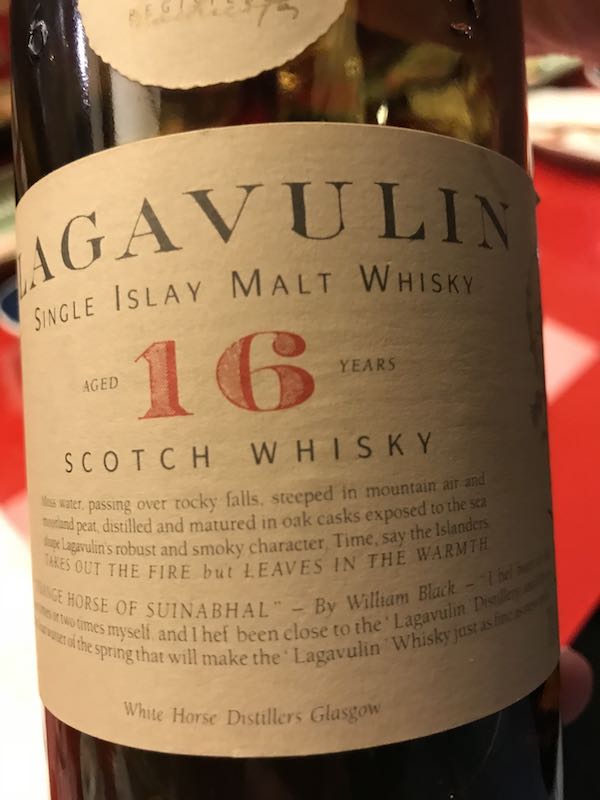

Whisky lovers know that there is a difference between old and new liquids. When I say old liquids, I do not mean whiskies that are aged 30 to 40 years old. I mean the liquids of old when times were different. A Lagavulin 16 years old made in the 1970s compared to one which is made now is different because the methods used in distilling, maturing and storing are all different.

The duo at WhiskyGeeks had the pleasure of trying a Lagavulin 16 Years Old made during the era of the White Horse Distillers. If you are aware of the history of Lagavulin, you will know that James Logan Mackie & Co bought the distillery in 1862 and refurbished it. When James Mackie passed away in 1889, his nephew, Peter Mackie took over and launched the White Horse range. When Peter Mackie died, the company changed its name to White Horse Distillers and controlled the distillery in that name from 1924 to 1927. The company sold the distillery to DCL in 1927.

Given the timeline, a bottle of Lagavulin 16 years old that holds the name “White Horse Distillers” in its label is likely to exist since their time? Not necessary. This bottle that we tried came from the 1990s. In 1988, Lagavulin 16 Years was selected as one of the six Classic Malts, and this bottle was one of the first few batches where Diageo still puts “White Horse Distillers” on the label. They phrased it out in the late 90s and also changed the crest on the label. We had the pleasure to try this because of our friend, Michael, whom we met for dinner during our trip to Taiwan. It is too special not to share the tasting note, isn’t it?

So let’s dive in!

Colour: Gold

ABV: 43%

Nose: Lemon peels, orange peels, citrus, brine and green apples presented themselves at the forefront. Hints of vanilla linger in the background. There is no peat evident in the nose; neither are there sharp or biting notes of spice. We can nose this all day long. (17/20)

Palate: Oily mouthfeel with sweet orange peels, lemon peels and green apples in the palate. Gentle spice and peat mix with the citrus sweetness. Then vanilla cream appears in the palate. It is almost like eating vanilla cream puffs! (19/20)

Finish: Medium finish with very gentle and sweet vanilla lingering all the way to the end, while the citrus sweetness waft in and out. The gentle peat blows over the mouth like a smoke cloud, almost difficult to catch. (17/20)

Body: Wow! This is most unlike the modern Lagavulin 16! The gentle peat and the vanilla sweetness are so unlike the modern version that we are blown away! It is very balanced too. Out of this world, indeed! (36/40)

Total Score: 89/100

Geek Flora: “Well, I did not know I was drinking a piece of history until I knew about the era of the bottle. After I know, I sipped the liquid more carefully than ever. Haha…very grateful to Michael and his friend at 常夜燈 for the chance to try this expression of the Lagavulin 16.”

Geek Choc: “I am flabbergasted. It tasted so different from the regular Lagavulin 16! Haha…amazing bottle with fantastic liquid!”

11311 Harry Hines Blvd

Dallas, TX, United States

(555) 389 976

dallas@enfold-restaurant.com